What You should Know About The Ọlọ́jọ́ Festival:

Why the Ọọ̀ni Wears The Sacred Crown Only Once a Year

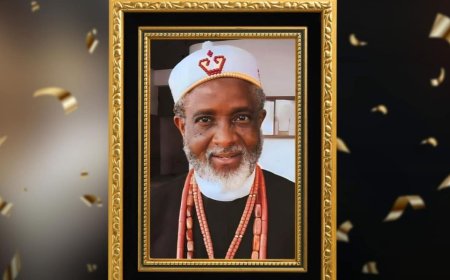

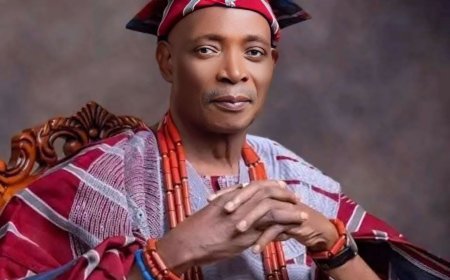

By late afternoon, the heat had softened and a careful hush drifted across Enuwa Square at the cradle of Ile-Ife. White garments flickered in the light, the drums fell to a watchful murmur, and faces turned towards the palace gate. The Ọọ̀ni of Ifẹ̀, Ọba Adeyeye Enitan Ogunwusi, CFR, Ọjaja II, stepped forward after seven days of seclusion, and the Aare crown rose above the crowd like a slow comet of beads anqd iron. In that instant, the city held its breath. Once a year, and only once, the crown comes out. Once a year, the ruler accepts its weight, blesses his people, and walks the ancestral road to the shrines that made Ile-Ife a cradle of civilisation.

The 2025 Ọlọ́jọ́ Festival stretched across a full week of public events, from Thursday, 25 September to Monday, 29 September, although preparations and private rites had begun earlier. On Friday, 26 September, the Ọọ̀ni ended his seclusion and offered prayers for the country. On Saturday, 27 September, he appeared with the Aare crown for the grand cultural procession known as Ojo Okemogun. Sunday, 28 September brought receptions, exhibitions and civic awards. Monday, 29 September closed the season with ancestral rites and the final of a cultural talent hunt. The week formed a steady arc from silence to splendour, from private devotion to public blessing, and it unfolded in real time before local and national audiences.

To understand why the crown matters, begin with what Ọlọ́jọ́ claims. In Yorùbá, Ọlọ́jọ́ means “the Day of the First Dawn”, the moment creation moved from darkness into light. Each year, the city retells that beginning. It is an act of gratitude for life and time, and for the power that set the world in motion. The festival is not a quaint survival. It is a cosmology brought into the square. In that light, the Ọọ̀ni's seven-day withdrawal is not theatre. It is preparation, so that the prayers he brings back carry weight.

The crown sits at the centre of that meaning. Palace tradition describes the Aare as the Ọọ̀ni's inherited symbol of authority. It is made, in legend and in craft, from iron and from elements linked to Ògún, the deity of iron, making and first paths. Oral accounts say the crown contains 149 undisclosed objects. It is worn only during Ọlọ́jọ́ . When it appears, people gather to look upon it, to pray in its presence, and to ask for peace, unity, blessing and prosperity. These are not museum labels; they are living claims, tended by the court and by those entrusted with the rites. The precise weight is reported in different ways, often “about 50 kg” and sometimes more. What the public record agrees on is simple enough: the crown is heavy in the body and heavier in meaning.

Because Ọọ́jọ́ re-enacts a first dawn, it renews Ilé-Ifẹ̀’s place in the world. Ifẹ calls itself the source, the place where Oduduwa founded kingship and where the Yorùbá trace a beginning. That memory is mythic, yet history nods in agreement. In 1938, builders at Wunmonije Compound struck metal and uncovered a cache of copper-alloy heads, cast with startling naturalism by the lost-wax method. The discovery unsettled a world that had once dismissed the depth of African courtly art. One of those heads now stands in the British Museum. Art historians use it to tell a different story of medieval Africa: courtly life, specialised workshops, and a tradition of portraiture that did not need Europe to breathe. Each Ọlọ́jọ́, when the Aare crown rises and the Ọọ̀ni walks, that story leaves the gallery and becomes a city speaking for itself.

The week was paced like a good procession. Thursday opened with traditional games and a colloquium, early gatherings that drew elders, students and visitors into a rhythm of learning as well as spectacle. Friday’s rites included Iwode Ife, a community cleansing that threads through the streets, and that evening the Ọọ̀ni prayed for Nigeria’s peace and unity as crowds swayed under floodlights. Saturday formed the fulcrum. Ojo Okemogun carried the crown into the open air, chiefs with chalk-marked swords took their stations, and drums answered one another in layered cadences. Only the Ọọ̀ni danced to the Osirigi drum, for there are sounds reserved to rank, just as there are paths reserved to office.

The route matters because the route is a map. From the palace, the procession moves towards the Okemogun Shrine, the old ground of oaths and iron where the Aare crown is confessed to Ògún before it is shown in public. There the ruler renews vows to land and people. There the Araba, the chief priest, performs divination at the foot of Oketage hill. There the city places its year on the anvil of ritual and asks that it be shaped well. These stops are not for show. They are points where memory lives.

Around the rites, the city made space for play and for pride. A first-ever Athletics Federation of Nigeria recognised Ọlọ́jọ́ 5 km road race brought elite distance runners to Ile-Ife. Ismail Sadjo won the men’s race in 15 minutes 15 seconds, and Affigbo Esther Chihurumnanya won the women’s in 17 minutes 38 seconds, each earning a one-million-naira prize. It is an openly modern addition, a runner’s dawn beside the ritual dawn. The organisers have been clear about the lesson. Heritage does not weaken when healthy civic life grows around it.

International readers often ask whether the Aare crown is like the British Crown Jewels or Japan’s imperial regalia. The likeness holds only at a distance. All royal objects seek to condense a people’s history and place it on human shoulders. The Yorùbá case adds something distinct. The Aare’s heart is iron, which belongs to Ogun’s world of forges, tools and first cuts. In a century still built on metal and on the technologies that flow from it, the symbolism feels surprisingly modern. Creation requires making, and making requires discipline and risk. The festival sets that work apart once more, and the ruler bears the ethics of work along with the authority of office.

This year also showed how a festival can keep faith with its elders while learning a new register. Diaspora viewers followed livestreams and short reels. A colloquium framed the week with ideas. Exhibitions made room for textiles, photography and contemporary craft. Younger attendees tasted a tradition that belongs to them as well. The tone was not gatekeeping but guardianship, a promise that sacred spaces would remain intact even as the city opened its doors. That balance is hard. It asks for discipline from hosts and humility from guests. Ilé-Ifẹ̀’s answer was to treat Ọlọ́jọ́ as a covenant rather than a nostalgia fair.

None of this hides the tensions inside a living tradition. Nigeria is religiously plural. Some citizens are wary of rituals they do not share. Others worry that sponsorships and tourism might flatten what makes Ọlọ́jọ́ matter. Yet the city’s elders and culture workers have learned that secrecy alone cannot pass meaning on. Explanation is not desecration. A clear public explainer that sets out what seclusion means, why women from the Ọọ̀ni’s maternal and paternal lines sweep the palace, and where oaths are renewed, helps outsiders understand without stripping the rites of their dignity. Say what can be said plainly. Keep what must be kept. Trust good faith to do the rest.

If the myth of first dawn gives the festival its shape, the archaeology of Ifẹ̀ gives it ballast. Scholars teach the Ifè heads as masterworks of world art, and museum labels are more careful than they were. Those heads are not “African Donatellos”. They are Ifè, and that is enough. Their beaded veils, scarification marks and calm expressions point to a court that knew how to put power into form without draining it of humanity. When the Aare crown appears each year, it is easy to imagine those faces, cool and exacting, somewhere in the crowd. A city salutes its rulers, and the rulers salute a city older than the palaces they inherit.

For the Ọọ̀ni, the hardest work likely happens in the quiet. Seclusion runs for seven days. It is a refusal of speech, company and distraction. He prays for his people. He prays for the country. He has said in past years that he prays for the wider Black world that looks to Ifè as a source. When he returns, he brings a people’s requests with him. This year, he asked for unity and peace, and the city answered with singing. The pattern lasts because it is honest about need. No throne fixes hardship, yet any institution that gathers tens of thousands to breathe the same hope for an afternoon is doing a kind of public work that spreadsheets cannot measure.

What does the crown ask of those who look up at it? It asks for an ethic as well as a faith. Ọlọ́jọ́ is a festival of Ogun as much as it is a festival of dawn. It honours tools, effort and invention. In the myth, the first dawn did not drift into being. Someone cut the first path and hammered the first hinge between dark and light. In a city that now trains engineers and artists, traders and scholars, that image travels cleanly. Make something worthy, and make it straight. When the Aare passes, people reach out and pray aloud because the crown reminds them that blessings take root in a people who keep faith with their work.

The 2025 edition proved that the festival knows its own rhythm. The broader programme stretched across the second half of September. The public highlights sat neatly over the long weekend. The sporting event opened a fresh lane. The closing rites on Monday returned the festival to its source, not to a stadium or a stage but to the old shrines and the whispered names that carry Ilé-Ifẹ̀ forward. Colour and sound dazzle, yet the deeper praise belongs to the timing. The city turns a calendar page together. It names the first morning again. It sends its ruler back behind palace doors, the crown boxed away, and then it gets on with the work that the year demands.

For anyone meeting Ọlọ́jọ́ from afar, the easy mistake is to stop at the spectacle. Try not to. See instead a public philosophy that has survived wars, colonial administration and cultural whiplash. See a ritual that holds memory, making and moral responsibility together. See a city that has learned to let cameras in without letting secrets out. And see, finally, a crown that is heavy enough to hurt and holy enough to heal, a crown worn once a year so that it never hardens into ornament.

As the festival closed, the square thinned to families and traders, to small knots of pilgrims and schoolchildren in matching polos. The canopies came down. The drums were lashed and carried away. The last curls of dust lifted in the evening heat. Inside the palace, attendants moved with the quiet confidence of people who know their work. Somewhere behind a door, the Aare returned to its silence. It will sleep there for a year. When it wakes, the city will gather again to watch a man shoulder a story older than memory and carry it into the light. That is why Ilé-Ifẹ̀ draws people from far away. That is why the diaspora keeps late hours for livestreams. That is why the hush comes, reliably, just before the crown appears, because for a measured span of minutes the world feels new and the first morning breaks again.

What's Your Reaction?