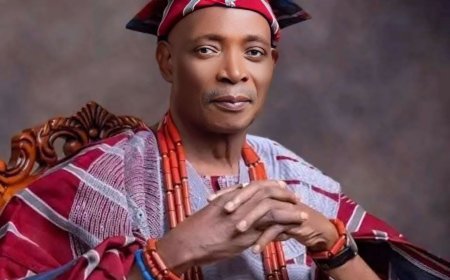

From Governor to King: How Rasheed Ladoja Rose to the Olubadan Throne

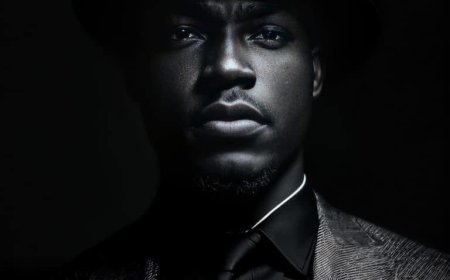

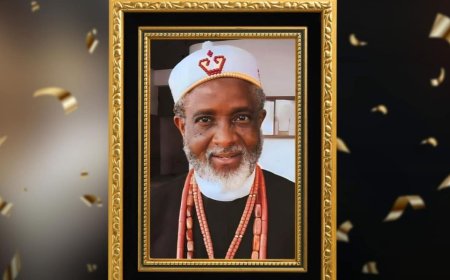

On a bright morning in late September, the city of Ibadan gathered in its thousands to witness a rare moment of history. At the foot of Mapo Hall, a colonial-era landmark that has long served as the civic heart of the city, drums rolled, chiefs arrived in flowing robes and feathered crowns, and dignitaries from across Nigeria filled the square. By mid-afternoon, Rasheed Adewolu Ladoja, once known nationally as a state governor and senator, was crowned the 44th Olubadan of Ibadan.

The coronation on 26 September 2025 came after the passing of Oba Owolabi Olakulehin, the 43rd Olubadan, who died in July. In Ibadan, a city of nearly four million people, the succession of kings follows a system that is unlike most monarchies in the world.

Who is the Olubadan?

The Olubadan is the traditional king of Ibadan, Nigeria’s largest indigenous city and the capital of Oyo State. Ibadan was once a formidable military power in the Yoruba world and remains a cultural and political hub today.

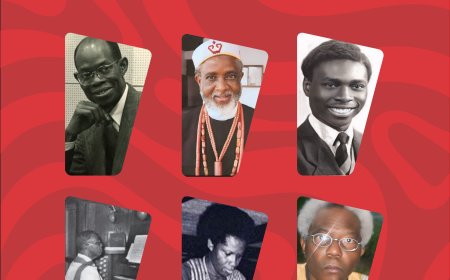

What makes the throne unusual is its succession process. Instead of being passed from father to son, kingship is determined by a slow, merit-based climb through the chieftaincy ladder. There are two lines of promotion: the civil line, called Ọtun, and the military line, called Balógun. Chiefs rise step by step over decades. Whoever reaches the top of either line and remains in good health is crowned Olubadan.

This system is regarded as one of the most orderly and transparent in Nigeria, since every chief knows exactly where he stands in the line of succession. It also means that Ibadan kings are usually older men with long careers in politics, business or public life before reaching the throne.

Although the Olubadan has no constitutional authority, he holds immense influence as the custodian of Ibadan’s heritage. His voice carries weight in community disputes, cultural preservation and even political negotiations, and coronations draw national attention from politicians, traditional rulers and ordinary citizens alike.

For Ladoja, who began his climb decades ago, his coronation was a reward for patience and endurance. That endurance has defined his career. In 2006, during his time as governor of Oyo State, he was impeached in a bitter political struggle, only to be reinstated by a court ruling eleven months later. The episode cemented his reputation as a man who could withstand storms and return stronger. Many Ibadan residents now see the same quality in the long years he has waited for the throne.

Humility is another trait often associated with him. In 2024, when he received a ceremonial crown from the late Olakulehin, he prostrated fully before the monarch in a gesture that struck many as deeply symbolic. At his own coronation, he bowed before ancestral shrines as priests poured libations in honour of past rulers, reminding the crowd that even a new king must first acknowledge the authority of history.

Yet Ladoja is not defined only by ritual. Trained as a chemical engineer at the University of Liège in Belgium between 1966 and 1972, he has long been described as a man who prefers analysis to slogans. During his years in politics, he was known for his reliance on technical reports and data, and people in Ibadan now expect him to apply that same measured approach to the demands of kingship.

The coronation was not only about tradition, but also about power. President Bola Ahmed Tinubu attended the ceremony, while Governor Seyi Makinde of Oyo State formally presented the staff of office. Governors Ademola Adeleke of Osun, Lucky Aiyedatiwa of Ondo and Biodun Oyebanji of Ekiti also came to pay their respects. They were joined by former governors Olusegun Mimiko, Donald Duke and Olagunsoye Oyinlola, as well as former senators Ibikunle Amosun and Gbenga Daniel. From the royal circle came the Sultan of Sokoto, Saad Abubakar, the Aláàfin of Oyo, Abimbola Owoade, and the Oluwo of Iwo, Abdulrasheed Akanbi. Their presence underlined Ibadan’s place at the centre of Nigeria’s political and cultural life.

In his acceptance speech, Oba Ladoja pledged to safeguard Ibadan’s cultural traditions, from the Egungun masquerade festivals to the Osemeji and Oke-Ibadan festivals, while also insisting that the throne must play a role in modern life. He spoke of heritage tourism, the preservation of oral history through digital archives and the inclusion of young people in cultural and economic opportunities. In doing so, he suggested that the monarchy should be both a custodian of the past and a participant in shaping the future.

Challenges will not be far away. Nigeria is struggling with economic uncertainty and political division, and in such times, traditional rulers are often called upon to steady their communities. Ladoja’s past controversies are well known, including investigations by the country’s anti-corruption agency, but at his coronation, he addressed the issue directly. “Corruption is the greatest barrier to progress,” he told the crowd, inviting elders and chiefs to hold him to account.

What sets Ibadan’s monarchy apart is its sense of time. Politicians may think in terms of four-year cycles, but an Olubadan is expected to think in generations. Ladoja made this point himself, saying that real progress will not be measured in months or even years, but in the decades to come. For a city that has endured wars, colonial rule, political upheavals and the pressures of rapid urban growth, the message was reassuring.

As evening settled over Mapo Hall and the crowd began to disperse, Ibadan carried home more than the memory of a coronation. It carried a renewed sense of expectation. In Oba Rasheed Adewolu Ladoja, the people saw a man who embodies resilience and humility, intellect and tradition, diplomacy and moral courage. If he fulfils that promise, his reign will not only shape Ibadan’s future but also remind the wider world that in Nigeria’s largest indigenous city, kingship is still alive, and still deeply relevant.

What's Your Reaction?