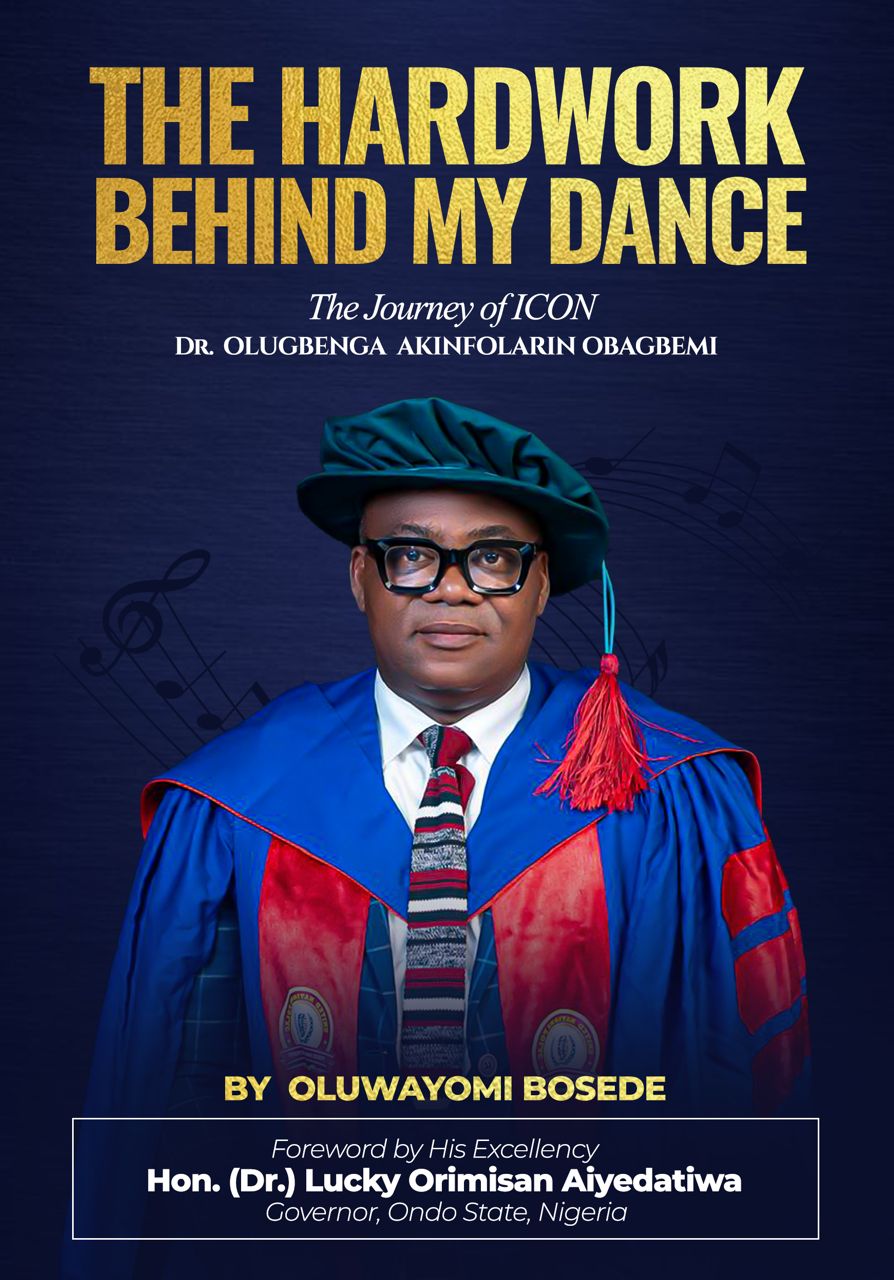

Oyotunji ! The Mysterious Yoruba African Village in America.

Hidden behind the pines of South Carolina, a living Yoruba kingdom keeps language, ritual, and royal custom alive with working temples, monthly festivals, and a community that has survived half a century of change.

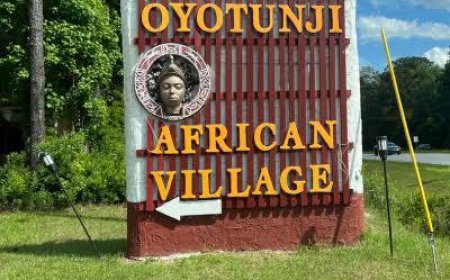

Drive past the marsh grass of Beaufort County and the scenery feels familiar: live oaks, sandy lanes, clapboard houses. Then a painted gateway appears and the atmosphere tilts. The sign reads Oyotunji African Village. Inside, courtyards open to the sound of drums. Shrines glow with candles and chalked symbols. Hand-painted boards point towards a palace square where proclamations once rang out. This is not a theme park. It is a working community that practises Yoruba culture on American soil.

The vision that became a village

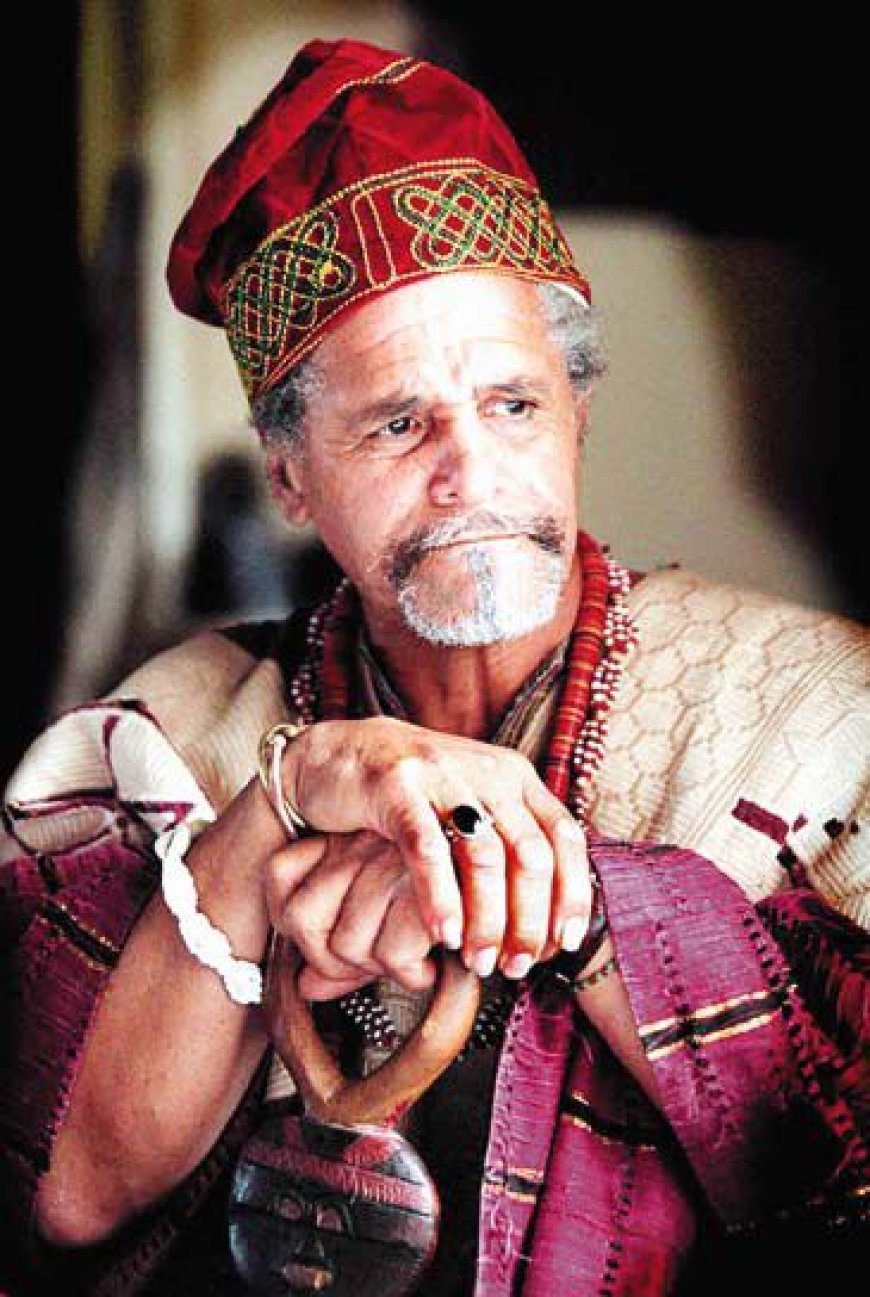

Oyotunji was founded in 1970 by Oba Efuntola Oseijeman Adelabu Adefunmi I. Born Walter Eugene King in Detroit, he began studying Afro-Haitian and ancient Egyptian traditions as a teenager and later came under the influence of the Katherine Dunham Dance Troupe in New York. A 1959 trip to Cuba led to his initiation into the orisha priesthood. He returned to the United States with a new name and a clear mission. In 1960 he founded the Yoruba Temple in Harlem. That temple became the cultural and religious forerunner of Oyotunji and, according to village accounts, was later relocated to South Carolina, where a new settlement was taking shape.

By June 1970 Adefunmi and a small band of followers had carved out a home in the Lowcountry. They intended to build in Savannah, Georgia, but settled near Sheldon after disputes with neighbours over drumming and a stream of curious visitors. The new community took the name Oyotunji — “Oyo rises again.” It was designed to echo the form of Yoruba city-states in Nigeria, with a palace for the king, temples for Obàtálá, Ṣàngó, Òṣun, Ògún, and others, and an annual cycle of festivals.

Growth, numbers, and the land

The site covers 27 acres (11 ha). In the 1970s the population grew from a handful of pioneers to somewhere between 200 and 250 people. Over the past decade, it has often been described as a small settlement of five to nine families, a population that fluctuates with work, study, and the seasons.

In 1966 Adefunmi created the African Theological Archministry (ATA) as an umbrella for training and governance. He also established a lineage known as Orisha Vodou to underline the tradition’s African roots. More than 300 priests are said to have been initiated through this network. In 1980 the state granted the Archministry a formal charter, which gave the village firmer legal footing.

Monarchy, continuity, and a hard year

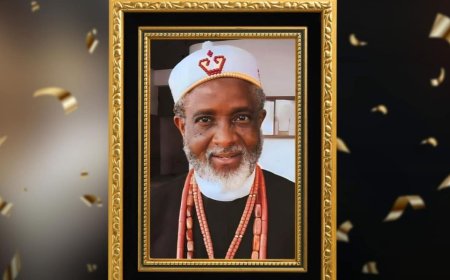

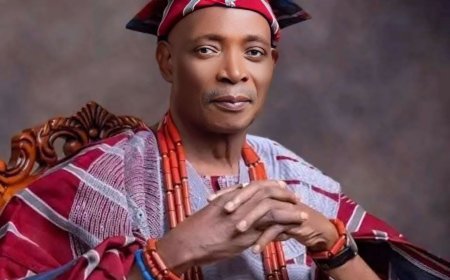

Oba Efuntola Oseijeman Adelabu Adefunmi I reigned from 1970 until his death in 2005, establishing the palace, priestly councils, and the festival calendar that still gives Oyotunji its rhythm. His son, Oba Adejuyigbe Adefunmi II, took the crown and kept the rituals steady while modernising elements of village life and public works. Day-to-day stewardship is now associated with Baba Imese Omobolanji, who is widely described as the current custodian, while the royal family states that Prince Adesina-Aremo, the Crown Prince, will ascend the throne at the appropriate time in line with divine guidance and family tradition.

The past year has tested that continuity. In July 2024, Oba Adejuyigbe Adefunmi II died after a stabbing during a domestic dispute; law-enforcement reports named his sister, Akiba Kasale Meredith, as the alleged assailant, and the case has been moving through the courts. Through the shock and the headlines, priests kept the drums and ceremonies on schedule, and visitors continued to find the gates open on festival weekends.

Amid rumours and competing statements, the Adefunmi Royal Family issued a public press release, signed by Her Royal Highness Yeye Oba Fabunmi Adesoji-Akinsegun Adefunmi-Sands, denouncing unauthorised individuals who had presented themselves as village spokespeople and engaged dignitaries in Nigeria without consent. The family clarified that Oyotunji currently has no official spokesperson or Baba Oba, urged the public to rely on its formal channels, and acknowledged heightened attention following the passing of Chief Lukmon Selelmon Arounfal shortly after a visit to the newly installed Alaafin of Oyo, Oba Abimbola Akeem Owoade. Reaffirming Oyotunji’s identity as an extension of the Oyo world, rooted in Dahomean and Yoruba bloodlines and linked spiritually to Ile-Ife, the family underscored its succession position: the Crown Prince will take the stool when the time is right.

Time measured by drums

Visitors quickly learn that Oyotunji keeps time by festival. A typical public calendar features:

• Yoruba New Year: purification, prayers, and a communal feast.

• Olókun Festival: devotion to the spirit of deep waters, with white and blue garments and stately dance.

• Èṣù, Ògún, Ọ̀sọ̀ọ̀sì: a vibrant sequence honouring the crossroads, iron and war, and the hunt.

These are acts of worship. Priests and priestesses lead the rites. Diviners work with opele chains or sacred palm nuts. Modest dress is expected in temple spaces. A small bazaar usually springs up around festival days with beads, cloth, herbs, carved gourds, and booklets written by residents.

What you will actually see

• The gate and signage: Yoruba proverbs and symbols set the tone the moment you arrive.

• Temples: painted façades, chalked floor designs, pots and altars inside; photography is often restricted.

• Courtyards: public rites and drumming unfold in the shade.

• Craft stalls: cowries, beadwork, textiles, and herbal goods made by the community.

• Consultations: divination and spiritual counselling by appointment.

Practicalities are simple. Wear comfortable clothing that covers shoulders and knees. Bring cash for entry and the market. Ask before taking photographs. Some ceremonies are closed to non-initiates.

Why it matters

Cultural reclamation: Oyotunji offers structured ways to learn Yoruba language, liturgy, and etiquette from practising priests.

Religious freedom: The village secured public space for orisha worship long before it was widely understood.

Diaspora dialogue: Links to Nigeria, Cuba, and Haiti have helped align American practice with established canons while accepting local realities.

Education and tourism: School groups, researchers, and travellers meet Yoruba culture as a living tradition rather than a museum exhibit.

Questions that keep the story honest

Every serious account should reckon with three recurring debates.

Authenticity and adaptation: What does a Yoruba city look like in coastal South Carolina, and how has that answer shifted with each generation?

Scale and sustainability: Small populations make leadership transitions and maintenance demanding. Festivals, tours, and offerings keep the lights on.

Representation: Journalists sometimes chase the exotic. The community repeatedly asks for coverage that centres worshippers, not spectacle.

If you go

• Where: near Sheldon and Seabrook in Beaufort County, South Carolina. Search “Oyotunji African Village” for directions to the gate.

• When: weekends are best. Check the official calendar and book tours in advance.

• How long: a guided tour runs for about 60 to 90 minutes; festival days can fill an afternoon.

• Etiquette: greet elders, remove hats in designated spaces, follow dress guidance, and ask before photos.

• Support: bring cash for entry, market purchases, and donations to temple upkeep.

The line that lingers

Oyotunji is not an artefact. It is a lived answer to a difficult question: can an African city survive in the Americas and still feel like itself? For more than fifty years, on a few quiet acres ringed by pines and marsh, the answer has been yes. You hear it in the drums, you see it in the courtyards, and you meet it in the people patient enough to keep the calendar.

What's Your Reaction?