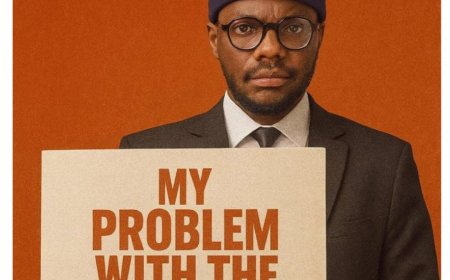

MY PROBLEM WITH THE “AFRO” PREFIX: RETHINKING AFRICAN IDENTITY IN GLOBAL MUSIC.

If you’ve been reading my write-ups for years, you would have noticed that I’ve always been uneasy with the way we throw prefixes around in music, prefixes that often serve no real purpose, some unnecessary, and others downright absurd. Take for example Gospel-Reggae or Gospel-Jazz, labels Christians use in an attempt to make certain genres sound “holier.” I’ve always resisted this boxing-in of music. I’ve even joked that I’ll only take these prefixes seriously the day I meet a Gospel-Lawyer, Gospel-Barber, Gospel-Banker, Gospel-Doctor, or even a Gospel-Carpenter. Until then, it remains, in my view, a misplaced obsession with branding rather than substance.

But this problem goes beyond the church. In the wider music scene, Africa has its own version of prefix-mania: the constant use of Afro- before almost every genre. Afro-HipHop. Afro-Soul. Afro-Trap. Afro this and that. Even Juju, which is already an African creation, has been renamed Afro-Juju by some. Just as I find Gospel-Jazz unnecessary, I find Afro-HipHop equally troubling. These prefixes often distort more than they define, and instead of strengthening our musical identity, they sometimes weaken it.

In the global music industry, labels carry power. They don’t just describe sound; they define identity, shape perception, and determine whether a genre is seen as original, derivative, or authentic. Over the years, this “Afro” prefix has become almost unavoidable whenever African artists engage with global sounds.

At first, the prefix seems harmless. It appears to signal pride in heritage, a way of announcing that this is music from the continent. But beneath the surface lies a troubling trend. The indiscriminate use of Afro- before every genre reflects a deeper insecurity: the need to personalize, localize, or sometimes even appropriate what has already been created, often to the detriment of clarity, respect, and authenticity.

HIPHOP: GLOBAL, YET SPECIFIC

Let us start with HipHop. Born in the Bronx in the 1970s, HipHop was forged by African American communities as both a cultural expression and a response to systemic oppression. It is deeply rooted in the lived experiences of Black America. When it crossed oceans, it didn’t lose its essence, it expanded. Nigerians rap differently from Americans, just as French or Japanese artists bring their own inflections. But the genre remains HipHop.

The problem arises when we feel compelled to rename it “Afro-HipHop.” The suggestion is subtle but significant: that what Africans create within the HipHop tradition is somehow separate, a parallel version that needs a qualifier. Yet when Canadians like Drake rap, it is not called “Can-Hop.” When British artists like Stormzy or Skepta spit bars, the world still calls it HipHop or Grime. No one insists on “Euro-HipHop.” Why then must African contributions be linguistically fenced off?

The “Afro” prefix doesn’t elevate African HipHop, it diminishes it. It implies that African rappers are not fully part of the global HipHop movement, but participants in a side genre that requires its own category.

THE JUJU PARADOX

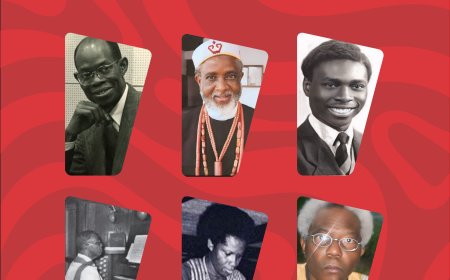

More puzzling still is the addition of “Afro” to genres that are already African. Take Juju, a proudly Nigerian creation. Juju’s roots run deep into Yoruba traditions and popular culture. To rename it “Afro-Juju” is not just redundant, it is confusing. It’s as if Europeans decided to call Opera “Euro-Opera” or Americans labeled Jazz “Ameri-Jazz.” These genres are so deeply tied to their origins that prefixing them feels absurd.

When we prefix African genres with Afro, we risk suggesting that they are somehow incomplete or undefined without the stamp of continental identity. Yet Juju doesn’t need external validation. It is already African, already ours, already legitimate.

THE DOUBLE STANDARD OF AFROBEATS

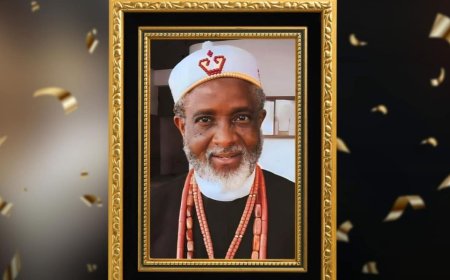

The irony becomes clearer when we look at Afrobeats. (Not to be confused with Fela Anikulapo Kuti’s Afrobeat) Today’s Afrobeats—popularized by stars like Burna Boy, Wizkid, and Davido, has taken the world by storm. And here lies the double standard: everywhere else in the world, the genre is respected by its African name. Whether it’s played in New York, London, or Seoul, it is simply called Afrobeats.

No American artist has tried to rebrand it as “AmeriBeats.” No European DJ has insisted on “EuroBeats.” Even Koreans performing it don’t call it “KoreBeats.” They respect the genre’s identity as African. But when it comes to HipHop or even Juju, we impose the “Afro” tag ourselves, as though Africa’s contributions must always be marked, separated, or explained away.

WHAT WORDS REVEAL

This matters because words shape perception. By prefixing Afro onto every borrowed or native genre, we unintentionally reinforce a damaging narrative: that African musicians are outsiders in global traditions, or worse, that African genres are not whole unless marked by a label.

Instead of “Afro-HipHop,” why not simply say HipHop from Nigeria, Ghana, or South Africa? Instead of “Afro-Soul,” why not call it Soul music infused with African influences? Instead of “Afro-Juju,” why not just honor Juju for what it is, a genre with roots no one can dispute?

We don’t need a linguistic crutch. Our music doesn’t become more valid with Afro stamped onto it. On the contrary, constant reliance on the prefix risks weakening our cultural authority.

African musicians and critics alike must ask: who truly benefits from the endless multiplication of “Afro” genres? Does it help African artists gain recognition, or does it serve industry gatekeepers who prefer to market African work as exotic, other, or niche?

The world already recognizes Afrobeats as Africa’s gift to the globe. Likewise, HipHop recognizes and respects its African American origins without denying global participation. Juju, Fuji, Highlife, and other African genres need no extra prefix to assert their identity.

What Africa needs is not more “Afro-labels” but more confidence. Confidence to stand firm in the knowledge that when we rap, we are HipHop. When we innovate, we are creators, not imitators. When we export genres like Afrobeats, we set the terms, not the other way around.

Africa’s musical heritage is rich, diverse, and globally influential. But every time we prefix “Afro” unnecessarily, we risk diluting our cultural legitimacy. Instead of carving out artificial categories, let us embrace the reality: Africa doesn’t need to over-explain itself in music or in any other area for that matter. We need to remember, civilization started with us, Africa is the motherland, we don’t play second fiddle. Before the rest of Europe knew how to treat ailments, Imhotep had diagnosed and treated over 600 ailments. Centuries later, Greek philosophers and physicians such as Hippocrates, Pythagoras, Plato, and Herodotus studied in Egypt, where Imhotep’s legacy as a physician and thinker was part of the intellectual heritage. Never forget that.

We are Africa! We belong to the world’s musical traditions just as much as the world belongs to ours.

By respecting our own genres as they are, and by claiming our rightful place in global ones, we strengthen, not weaken the authority of African voices in the world’s musical tapestry.

Ngwa Gwazie Ndi Yard Unu!

Dieko Obi

I have written again.

What's Your Reaction?