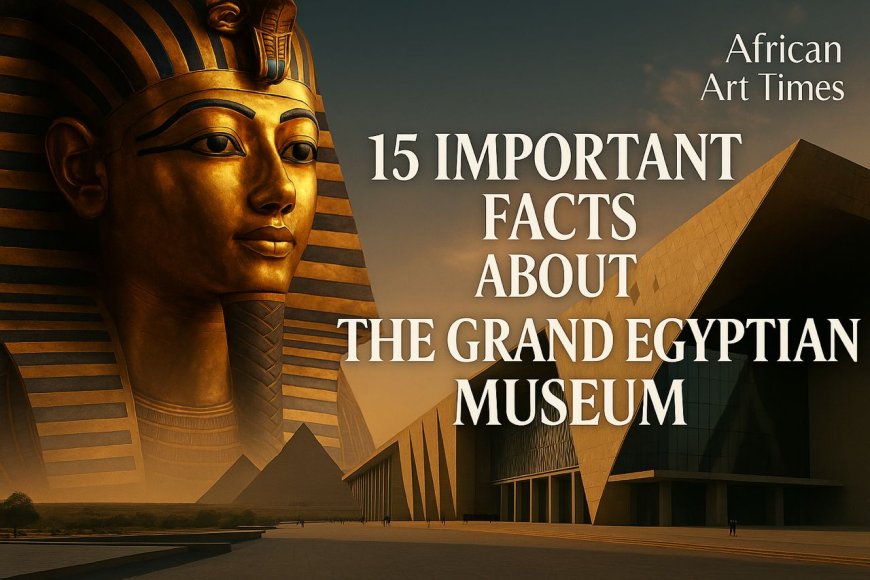

15 Important Facts about the Grand Egyptian Museum

For more than twenty years, the Grand Egyptian Museum existed mainly as a promise. Dates were announced and revised, cranes came and went, and the world kept watching the Giza Plateau, waiting for something new to join the pyramids on the skyline. Now it has happened. On the western edge of Cairo, Egypt has opened the doors of the largest archaeological museum on earth, a project that has absorbed more than US$1 billion and an entire generation of planning, building, conservation, and debate.

The Grand Egyptian Museum (GEM) is not simply a replacement for the old Egyptian Museum in Tahrir Square. It is a cultural district at the edge of the desert: galleries, laboratories, gardens, performance spaces, classrooms, cafés, shops, and research centres gathered into one vast, carefully choreographed space. It sits within a wider continental movement as well. Alongside newer institutions in Dakar, Cape Town, Lagos, Kigali, and other cities, the GEM shows how African countries are building flagship museums at a level that can stand beside any in the world, on their own terms.

For African readers, and for anyone who cares about history and design, these fifteen facts explain why the GEM matters and what makes it unlike any other museum on the planet.

A Twenty-Year Journey With a Billion-Dollar Price Tag

The idea of a new museum at Giza was already circulating in the 1990s. An international architectural competition was held in 2002, construction began in 2005, and the project then had to survive a revolution, economic shocks, leadership changes, and a global pandemic before its formal inauguration.

The cost is estimated at more than US$1 billion. That figure reflects a long-term vision rather than a simple building contract. It covers the architecture, the conservation centre, the movement and treatment of thousands of objects, and the creation of an entirely new visitor infrastructure at Giza.

Egypt chose to invest at the scale of a national airport or a major transport hub, not in roads or runways, but in a museum.

The Largest Archaeological Museum on the Planet

The GEM occupies a site of about 500,000 square metres, roughly 50 hectares of land. That footprint is larger than many historic city centres. It has become the largest archaeological museum in the world and the largest devoted to a single civilisation.

Within that footprint sit twelve permanent galleries, the Tutankhamun complex, a purpose-built boats museum, the conservation and research centre, a children’s museum, education facilities, a library, cinemas, an auditorium, conference spaces, restaurants, and shops. The remaining space is given to plazas, promenades, and planted areas.

This scale allows objects to breathe. Colossal statues stand in open halls rather than being squeezed into corners. Visitors can move through the building without feeling crushed by crowds, even on busy days.

A Museum Written Directly into the Giza Horizon

The GEM is not just near the pyramids. It is in conversation with them. The building stands at El Remayah Square on the western edge of Cairo, within the UNESCO-listed landscape of ancient Memphis and its necropolis, and its geometry has been aligned with the three pyramids of Khufu, Khafre, and Menkaure.

The northern wall, the southern wall, and the main internal axis follow sightlines that point towards the pyramid silhouettes. From the Grand Hall and from the top of the Grand Staircase, visitors look out through glass to see the pyramids framed like sculptures in a giant window.

From outside, the museum’s angular façade echoes the forms of the desert plateau. The result is a new architectural presence that does not compete with the pyramids but settles beside them respectfully.

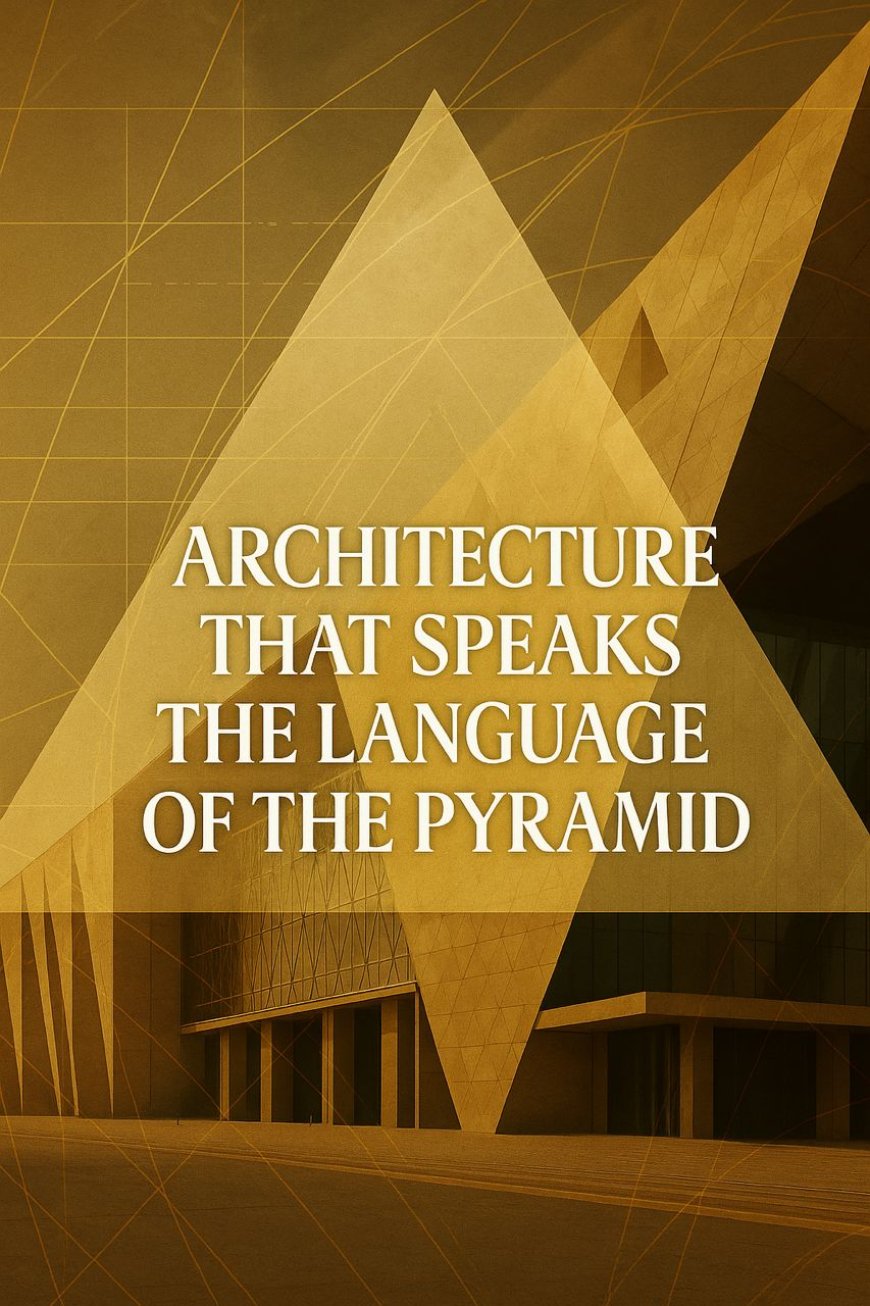

Architecture That Speaks the Language of the Pyramid

The design by Heneghan Peng Architects takes the triangle as its basic unit. The main façade is a long stone screen composed of triangular panels. Behind it, a series of recessed courts are shaped like hollow pyramids, bringing light deep into the building. Larger pyramid forms project from the façade and glow at night.

Inside, ramps and bridges create long vistas. Visitors catch repeated glimpses of the desert beyond, then return to the carved stone and controlled light of the galleries. The building never lets you forget where you are.

The museum’s visual identity follows the same logic. Its logo uses simple lines to echo the rising profile of the building, the edge of the plateau, and the geometry of the pyramids. Architecture and branding tell the same story in different scales.

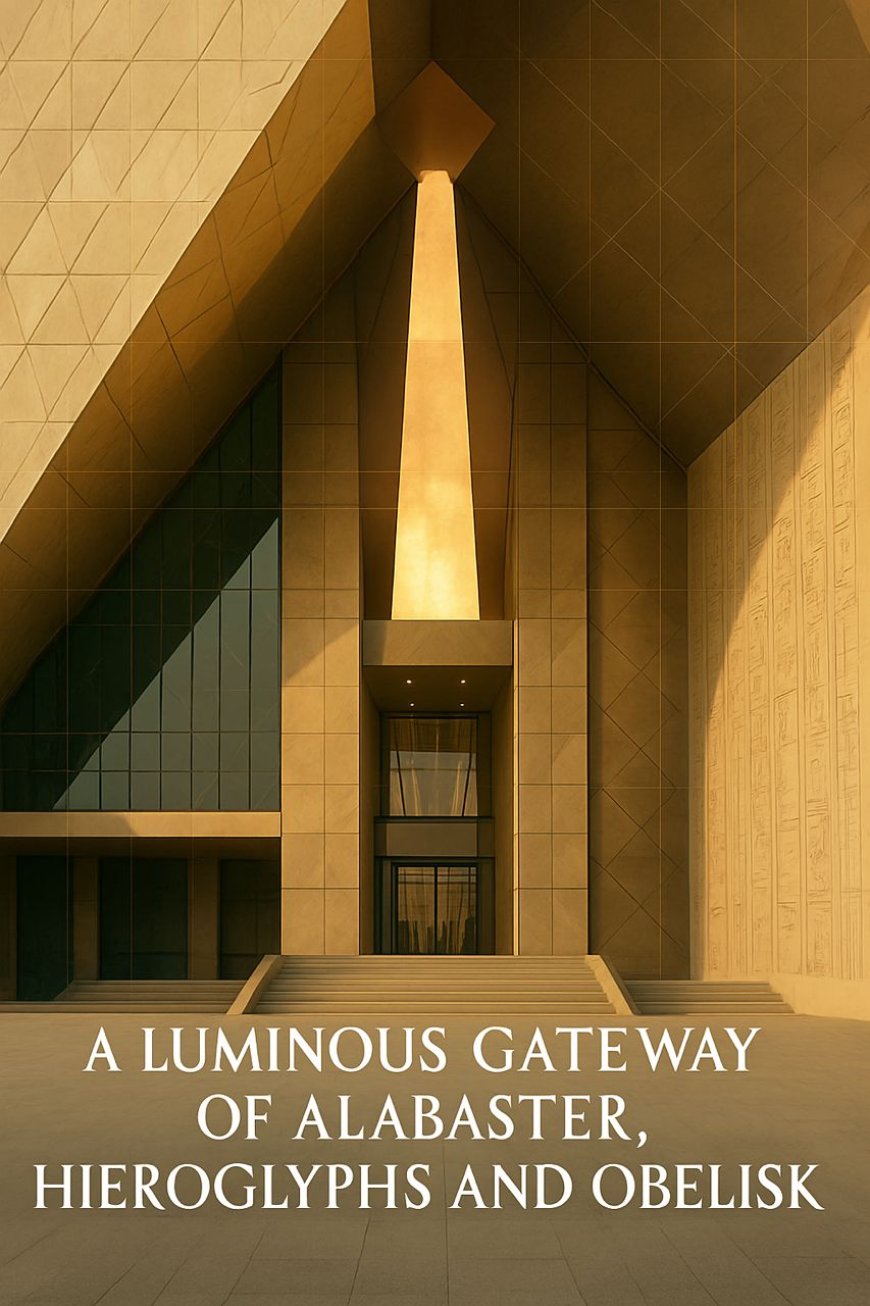

A Luminous Gateway of Alabaster, Hieroglyphs, and Obelisk

The entrance sequence to the GEM has been designed as a piece of theatre. Visitors walk across a wide open plaza towards a gateway clad in pale alabaster. The stone catches the sun and glows softly at dusk, recalling the bright casing stones that once wrapped the pyramids themselves.

Near the entrance stands a suspended obelisk of Ramesses II from the ancient city of Tanis. It is displayed in a new way. Raised on a granite cradle with glass beneath, it allows visitors to pass under the shaft and look up at the carved royal names on the underside, an angle few would ever have seen in antiquity.

At the threshold, a monumental wall of hieroglyphs lists some of Egypt’s most famous kings and queens. The effect is ceremonial and personal. You step into the museum under the gaze of the ancient royal names, carved in the script that once filled temples and tombs.

Ramses II in the Grand Hall, Lit by the Sun of Abu Simbel

Just inside, the Grand Hall rises high enough to hold an eleven-metre statue without making it feel cramped. That statue is Ramses II, the great pharaoh of the nineteenth dynasty. For more than fifty years he stood in a traffic-clogged square in central Cairo, exposed to exhaust fumes and constant vibration. In 2006 he was moved in a carefully planned overnight journey to the new museum site. In 2018 he was shifted again, into the Grand Hall itself.

He now stands at the centre of the complex, where all routes seem to meet. Ticket desks, security points, gallery entrances, gardens, and staircases all radiate from his position.

The hall has been aligned so that on one chosen day in February, sunlight streams in and falls directly across his face, echoing the famous solar alignment at the Great Temple of Abu Simbel, which was also dedicated to him. It is a quiet but powerful link back to ancient ideas of kingship, the sun, and stone.

The Saqqara King List and a Staircase Lined With Giants

Sharing the Grand Hall with Ramses is another crucial object: the Saqqara King List. Carved more than three thousand years ago, it records the names of 58 earlier rulers in mostly chronological order. Found in the tomb of a high priest at Saqqara, it has become one of the key sources for reconstructing Egypt’s royal history.

Seeing it at the entrance of the GEM feels appropriate. You are greeted by the civilisation’s own attempt to remember itself.

From this hall, the Grand Staircase climbs towards the galleries and the glass wall that frames the pyramids beyond. The stair is not simply a way of moving between levels. It is an exhibition in its own right. More than fifty monumental artefacts line its steps and landings: colossal statues, sarcophagi, architectural blocks, and columns.

Walking up, you move between these giants and watch the relationship between stone and sky shift with every step. It is one of the building’s most memorable spaces.

More Than 100,000 Artefacts, Many Seen for the First Time

he GEM brings together more than 100,000 artefacts from museums and storerooms across Egypt. The collection stretches from the earliest prehistoric communities along the Nile to the Greco-Roman era. It includes pharaonic sculpture, papyri, jewellery, domestic objects, tools, coffins, reliefs, and architectural elements.

A significant number of these pieces have never been displayed to the public before. Some were too fragile to show in older buildings. Others were simply in storage because there was no room to exhibit them.

Their move to the GEM, supported by modern conservation, means that the story of Egypt is no longer told only through a familiar shortlist of masterpieces. Everyday items such as toys, sandals, and cosmetics appear alongside royal statues and golden shrines. The civilisation emerges as a full society rather than a parade of famous names.

Tutankhamun’s World Gathered Under One Roof

For many visitors, the highlight is the suite of galleries dedicated to Tutankhamun. For the first time, all the objects from his tomb are on display in one museum. More than 5,000 items from the burial fill a series of carefully lit rooms that follow the structure of the tomb and then open out into the wider world of the New Kingdom.

The famous gold mask, nested coffins, and gilded shrines are present, but so are the chariots, beds, chairs, linen garments, weapons, writing tools, board games, jars of food and wine, and personal amulets.

Together they tell a story not just of royal splendour but of craft, trade, technology, and belief. They reveal the amount of labour, wealth, and imagination poured into the preparation of a single burial, and they do so in a setting that finally matches the importance of the objects.

Boats, Queens, Soldiers, and the First Pyramid Builders

Elsewhere in the museum, focused collections bring individual stories to life. The Khufu boats, associated with the builder of the Great Pyramid, show in striking detail how large wooden vessels were made without metal nails. One royal solar boat has been reconstructed from thousands of cedar fragments. The second was moved to the GEM in a delicate engineering operation that became a conservation project in its own right.

Nearby, the jewellery of Queen Khnemmetneferhedjet Weret II glows with gold and brightly coloured inlays. Each piece carries layers of symbolism, from protection and rebirth to power and status.

The Mesehti collection offers wooden models of soldiers and boats from the Middle Kingdom, small figures that nevertheless reveal much about military organisation and life on the river. From the Step Pyramid complex of King Djoser come 36 stone vessels, carved with great skill in the early days of monumental stone architecture. Their quiet forms anchor the story of pyramid building at its beginning.

A Conservation Powerhouse with Nineteen Specialised Laboratories

Behind the public areas lies one of the museum’s most important features: the Conservation Centre. This complex of nineteen laboratories is dedicated to different materials and tasks. There are laboratories for organic materials, textiles, wood, metals, ceramics, glass, papyrus, pigments, and human remains, as well as spaces for scientific analysis and digital documentation.

Conservators examine objects under microscopes, run chemical tests, design mounts, clean and stabilise surfaces, and monitor the climate conditions in the galleries. The centre also functions as a school. Young Egyptian specialists train there under senior experts, building skills that will support museums and archaeological sites across the country.

The GEM is therefore not only a place that shows heritage. It is a place that actively protects and studies it.

A Full Cultural Campus for Learning, Research, and Daily Life

The Grand Egyptian Museum has been designed as a place that people can use regularly, not only as a tourist landmark. A dedicated children’s museum introduces younger visitors to archaeology and history through play, experiments, and interactive installations. Education rooms host school groups, teacher training, and community workshops.

A library and reading rooms support researchers and students. A cinema and an auditorium host lectures, film screenings, and performances that explore Egyptian heritage and wider cultural themes. Conference facilities allow for international gatherings on archaeology, conservation, and cultural policy.

Beyond the academic spaces, cafés, restaurants, and shops highlight Egyptian cuisine, design, and craftsmanship. The intention is clear: to make the GEM part of everyday life for residents of Cairo and Giza as well as a destination for international visitors.

Immersive Technology, Nile-inspired Gardens, and a New Tourism Engine

Technology runs through the museum in a measured way. Augmented reality and projection are used to reconstruct damaged reliefs and temple spaces, to show how statues might once have looked in colour, and to allow visitors to explore tombs and sites virtually where physical access must be limited.

Interactive screens invite visitors to explore hieroglyphs, watch short films on construction techniques, and zoom in on high resolution images of delicate objects. Virtual reality experiences offer careful, guided immersion in spaces that may be too fragile for large numbers of people.

Outside, the open spaces are shaped as a contemporary echo of the Nile Valley. Bands of planting run between more arid surfaces, with shade, seating, and play areas. These spaces are intended for families, school groups, and evening events.

Taken together, the complex is expected to draw millions of visitors each year and to encourage people to spend more time in the wider Giza area. It is a cultural project and an economic engine.

A Public Commitment to Carbon Neutrality

The GEM has publicly committed itself to becoming a carbon neutral museum. In practical terms this means working with Egypt’s environmental authorities to measure and reduce emissions, improve energy efficiency, use more sustainable materials, and integrate renewable energy where possible.

The museum also plans to use its spaces to highlight Egypt’s natural reserves and protected landscapes, drawing a connection between cultural heritage and environmental stewardship.

This is an important signal. It shows that a major heritage institution in Africa can take a leading role in sustainability, rather than treating it as a secondary issue. Preserving a thirty-century-old statue and protecting twenty-first century ecosystems are presented as part of the same ethical commitment.

How to Visit, and Why the GEM Matters Beyond Egypt

The Grand Egyptian Museum sits on a main road network on the western edge of Greater Cairo. It is easy to reach from the city centre and from the pyramids, and it is served by taxis, organised tours, and local transport. Timed tickets help to manage visitor flow. Ramps, lifts, tactile models, and multi-sensory exhibits make the complex more accessible to visitors with different needs.

The deeper significance of the GEM, however, lies beyond logistics. For the first time, the full scale of ancient Egyptian civilisation is presented in a purpose-built, world-class museum on African soil, under African leadership. The treasures of Tutankhamun, the colossal statue of Ramses II, the vessels of Djoser, the jewellery of lesser-known queens, and the everyday objects of workers and children are all framed here by Egyptian curators, architects, and conservators.

For Africa, this is a reminder that the continent’s most powerful stories do not need to sit in European or American capitals to be seen, studied, and celebrated. For the rest of the world, it is an invitation to encounter one of humanity’s foundational civilisations in a setting that honours both its age and its ongoing influence.

Standing in the Grand Hall, with Ramses behind you and the pyramids on the horizon, you understand that this is not only Egypt’s museum. It is a place where Africa speaks for itself, in its own voice, to anyone willing to listen.

What's Your Reaction?